Advertisement

If you have a new account but are having problems posting or verifying your account, please email us on hello@boards.ie for help. Thanks :)

Hello all! Please ensure that you are posting a new thread or question in the appropriate forum. The Feedback forum is overwhelmed with questions that are having to be moved elsewhere. If you need help to verify your account contact hello@boards.ie

NUI to be dissolved

Options

Comments

-

Red_Marauder wrote: »I think youre wrong to look at points instead of actual places.

In 2007/ 08 there were 1,823 more new entrant first years at University for science, medical/ health, engineering and agricultural courses than there were for humanities, law, and business courses.

If there are more courses available, and more places available, this lowers the points requirements. On the whole there were more students studying medical/ engineering/ science/ agriculture than the "easier" courses.

http://www.hea.ie/files/files/file/statistics/HEAFacts0708(1).pdf

Not really. If more people go to college overall, then the points for any given course continue to reflect the proportion of students wishing to enter that course. Only if there were more places available in Science alone would the number of places affect the entry requirements for Science.

I suspect that if I do some research, I will find - college funding being what it is - that the number of places available for Science has actually decreased relative to the number of places available on less resource-demanding courses. I suspect that because it is a traditional move by universities in a funding squeeze, since the 'profit' per Arts student is much higher - indeed, the marginal cost of adding a couple more Arts students to a course is very little indeed.

cordially,

Scofflaw0 -

T.W.H Byron wrote: »I'm genuinely confused right now as I thought you were making a correlation between falling standards and falling CAO points for Arts and other subjects.

Sorry - no, I'm concentrating very specifically on the jump in higher awards that happened across Irish universities in 2002-2004. My comments on CAO points and LC grades is in response to this suggestion:I think it was movement of very intelligent students from courses with more subjective appraisal methods, with marking schemes normally following a curve, into courses with completely objective evaluation, courses with traditionally lower levels of 1sts and 2nds but courses that have to award everyone who gets the right answers down on the exam sheet the marks allotted for those particular questions. Such a shift probably would not have affected the scores of the more subjective degrees and hence the total overall number of higher degrees went up.

If someone suggests that the higher awards were the result of more intelligent students from courses with less subjective appraisal methods (eg Arts, Commerce) to courses with more objective standards (eg Science), then we should see evidence of that in the CAO points, which should go up for the more objective courses unless LC grades are falling. However, LC grades were rising, not falling, while points for 'objective' courses were falling. That's the complete opposite of what would happen if the suggestion above had merit.

The steep rise in Arts in UCC will be mirrored, I would think, by a steep rise in points requirements across the board over the last couple of years...hmm...yes, Science UCD from 300 pts in 2008 to 385 pts in 2009. That's hardly a surprise, since there's now very little prospect of getting a job at 18.

cordially,

Scofflaw0 -

There was probably no change in the teaching practices at all. What would have been seen though, I think, is a shift of brighter students into degrees traditionally thought of as very difficult due to the promise of new found opportunities because of the Celtic Tiger. Anyone graduating in 04, went in in 2000 and went through guidance counselling etc. in the couple of years before that, when engineering, computer science and health sciences were being touted as the areas in which bright students should forge a career.

What would have been the result? I think it was movement of very intelligent students from courses with more subjective appraisal methods, with marking schemes normally following a curve, into courses with completely objective evaluation, courses with traditionally lower levels of 1sts and 2nds but courses that have to award everyone who gets the right answers down on the exam sheet the marks allotted for those particular questions. Such a shift probably would not have affected the scores of the more subjective degrees and hence the total overall number of higher degrees went up.

On the subject of making degrees harder - that's not really possible, not to account for sudden and possibly short term trends anyway, as students need to be judged on what industries expect and there needs to be fairly uniform difficulty across college courses. For example, if a particular course in UCC was renowned because of it's facilites or whatever and drew in the best students then it could not sit harder exams to compensate and award 2.1s to students who would have easily gotten a 1.1 in another institute.

It will be interesting to see what happens in the next few years as the number of students tackling these "harder" courses drops off.

The implication of your thesis is that the increase in the number of 1sts and 2.1s in "science type" subjects should be much greater than the increase in the same grades for "arts type" subjects.

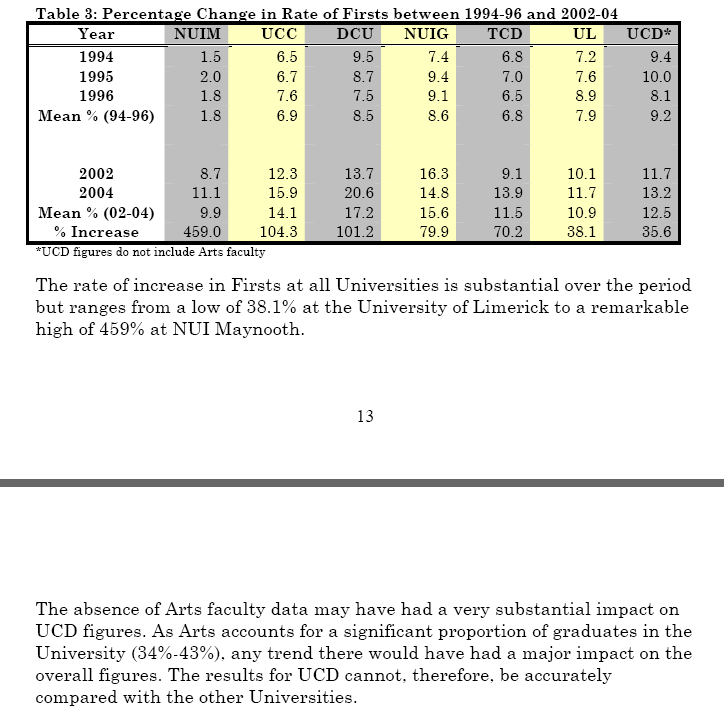

Now, we can get some idea if this might be true from the following table supplied by O'Grady and Guilfoyle

END OF EXCERPT

As we can see, the figures for UCD do NOT include the grades for the UCD Arts degree which accounts for a large percentage of UCD grads.

This means that the UCD figures mainly consist of "science type" subjects.

But instead of a larger than average jump in the percentage of higher degrees, UCD actually has the smallest increase.

Of course UCD is only one college but it's the largest one and it would be really surprising if it bucked the trend of all the other colleges. So it would appear in that in UCD at least, brighter students transferring to science type subjects did not cause a big jump in overall grades.

The other implication of your post is that there are no definite standards in Arts subjects and that in effect there has been massive grade inflation in those subjects; I guess that's where all the "Arts Degree -Please Take One" signs on college toilet roll dispensers came from:D

I think you're the second person to mention that Science type degrees are marked 100% "objectively".

At university level this is not really true, there is plenty of scope for "subjective marking".

For example:

A science question might ask the student to describe an experiment or a process - plenty of room for interpretation there.

A maths question might ask the student to solve an equation or prove a theorem.

So you can argue whether the student should only get marks for getting the correct answer or how much credit should they get for the solution process. What if they used a brilliant solution procedure that hadn't been taught on the course but made a small sign mistake that led an incorrect answer?

Similarly with a proof, do they get full marks for proving the result in any manner or should students who use a shorter proof or a more "elegant" proof get a higher mark?

How the examiner answers the above determines the final marks and of course has implications for grade inflation.

A question may also be composed of several parts and the examiner can decide how much weight to give to each part.

Most people would agree that a description type question is easier than a solution or proof question so if the examiner gives more weight to the description part, this will favour the hardworking but maybe less able student.0 -

This post has been deleted.0

-

donegalfella wrote: »This post has been deleted.

I see where you're coming from and I somewhat agree with you but, I don't really think the Leaving Cert and the points attained in it are any measure of intelligence or the potential workload that a student can take on. By all accounts I got a terrible terrible Leaving Cert result in 2003. When I say terrible I mean below the 250 points mark. Does that make me a moron?? Not in the least. Some people just dislike secondary school as I did and it didn't or doesn't challenge them. If you like something, you'll do well at it and you'll make the effort. I understand what you're saying though as some people just don't bother at all. I see it all the time in Arts in UCC, which is where I am now.0 -

Advertisement

-

T.W.H Byron wrote: »I see where you're coming from and I somewhat agree with you but, I don't really think the Leaving Cert and the points attained in it are any measure of intelligence or the potential workload that a student can take on. By all accounts I got a terrible terrible Leaving Cert result in 2003. When I say terrible I mean below the 250 points mark. Does that make me a moron?? Not in the least. Some people just dislike secondary school as I did and it didn't or doesn't challenge them. If you like something, you'll do well at it and you'll make the effort. I understand what you're saying though as some people just don't bother at all. I see it all the time in Arts in UCC, which is where I am now.

Again, nobody is actually setting out to criticise anyone here. A mark is rarely, if ever, the measure of the man (or woman) - as you say, if you like something, you'll make the effort. The guy who came bottom of my class, with a 2.2, was a far better field scientist than me, and went on to make a very good career, whereas I mucked about for a couple of years and wound up doing something completely different.It's also worth pointing out that he did the SAT, and scored something like 99.4%!

cordially,

Scofflaw0 -

This post has been deleted.0

-

donegalfella wrote: »This post has been deleted.

I'm obviously completely illiterate and an all round idiot so.0 -

This post has been deleted.0

-

donegalfella wrote: »This post has been deleted.

No, but you were implying that there is a correlation between high leaving certificate points and a high iq. Perhaps there is one, maybe not.

Maybe I am being overly defensive but that is because I am quite proud of what i've achieved in my life thus far, educationally speaking, considering my social background/upbringing and my lack of a good leaving certificate result. Some of the most intelligent people I know are the ones who got average at best results in the leaving cert.0 -

Advertisement

-

This post has been deleted.0

-

donegalfella wrote: »This post has been deleted.

But you've illustrated exactly what I was talking about in your post. In the late 1990s up to maybe 2001, 2002 at a stretch the points for Computer Science, Maths, Computer Engineering etc. have generally been at an historic high, meaning that there were more higher achieving students taking them. Very rapidly, from around 2001/02 onward these points fell as their was a massive decline in the technology sector and confirmation of the death of the "dot com" bubble. It was in the late 90s that telecoms consultants were pulling in a couple of grand a week.

Remember too that those points are only the minimum required for entry and courses like those which are generally unpopular simply because of the content and seen as "nerdy", the minimum points are probably further away from the mean points for entry than with other courses.0 -

-

But you've illustrated exactly what I was talking about in your post. In the late 1990s up to maybe 2001, 2002 at a stretch the points for Computer Science, Maths, Computer Engineering etc. have generally been at an historic high, meaning that there were more higher achieving students taking them. Very rapidly, from around 2001/02 onward these points fell as their was a massive decline in the technology sector and confirmation of the death of the "dot com" bubble. It was in the late 90s that telecoms consultants were pulling in a couple of grand a week.

Remember too that those points are only the minimum required for entry and courses like those which are generally unpopular simply because of the content and seen as "nerdy", the minimum points are probably further away from the mean points for entry than with other courses.

Again, though, what relevance does this have to the jump in grades in 2002-2004? We know that most of the grade inflation took place over that period, we know that that period was when the NUI changed its marking scheme. Your explanation isn't required - and as baalthor pointed out above, using the figure for UCD degrees without Arts awards gives the lowest rise, which exactly contradicts the idea that the grade increases resulted from 'more intelligent students in more objectively marked courses'.

cordially,

Scofflaw0 -

But that's my point - there are more places available for scientific courses (medical and medical sciences, pure sciences, engineering. and agriculture) at University level than there are for the humanities, law, and commerce.If more people go to college overall, then the points for any given course continue to reflect the proportion of students wishing to enter that course. Only if there were more places available in Science alone would the number of places affect the entry requirements for Science.

There are more courses under the 'science' bracket by 1.800 places. This makes it difficult to use points alone as an indicator of whether academically stronger students are entering science - because the courses with higher numbers are less sensitive to changes of this nature.

We do not have the figures for how undergraduate vacancies have altered in terms of science vs humanities - but yes I would certainly suspect you are correct that the number of humanities places has increased disproportionately for the reasons you outlined.

I would quite honestly be very sceptical for that reason that the academically high achieving students have been increasingly applying to scientific courses overall.0 -

Red_Marauder wrote: »But that's my point - there are more places available for scientific courses (medical and medical sciences, pure sciences, engineering. and agriculture) at University level than there are for the humanities, law, and commerce.

There are more courses under the 'science' bracket by 1.800 places. This makes it difficult to use points alone as an indicator of whether academically stronger students are entering science - because the courses with higher numbers are less sensitive to changes of this nature.

We do not have the figures for how undergraduate vacancies have altered in terms of science vs humanities - but yes I would certainly suspect you are correct that the number of humanities places has increased disproportionately for the reasons you outlined.

I would quite honestly be very sceptical for that reason that the academically high achieving students have been increasingly applying to scientific courses overall.

Sorry. - perhaps I should have been clearer - in order for the number of places to be the sole determining factor in a drop in the points requirement for science courses, the amount of science places would have to have been increasing by more than the proportional increase in arts places.

However, I think we're all agreed that there wasn't really a movement of better students into "more objective" courses. Together with the fact that it was Arts degrees (and, I'm willing to bet, particularly Commerce degrees) that actually enjoyed most of the grade inflation, that explanation clearly holds no water.

cordially,

Scofflaw0 -

However, I think we're all agreed that there wasn't really a movement of better students into "more objective" courses. Together with the fact that it was Arts degrees (and, I'm willing to bet, particularly Commerce degrees) that actually enjoyed most of the grade inflation, that explanation clearly holds no water.

cordially,

Scofflaw

Do you disagree that from 1998 through 2000 that points for many computer and technology related degrees were far higher than they are now or have been in the last 7-9 years. Do you agree that if this was so that it's possible such courses would have produced more higer grades in the period of 2002-2004? You say that the increase in grades was probably among Arts and Commerce courses? I'm curious as to why you have singled these courses out?0 -

Was the €3m saving really the reason for dissolving the NUI? There has been talk of this for some time now...

I don't have time for a hefty post, as I have much reading to do, so I will leave you with Colm McCarthy's thoughts:Minister Batt O’Keeffe announced this afternoon that the Government has decided to scrap the National University of Ireland. UC Dublin, UC Cork, NUI Maynooth and NUI Galway were the constituent colleges. The total number of universities in Ireland has thus been increased, at a stroke, from four to seven. Ireland should now soar up the universities-per-capita league tables.

Sadly, it will no longer be possible for the NUI to play the role envisioned for it in the 1950s by Flann O’Brien (Myles na Gopaleen). He ended an Irish Times controversy about academic snobbery and the excessive use of academic titles by proposing that NUI should simply confer doctorates on all Irish citizens at birth. Although the government appears to have embarked on a slower progress toward the same destination.

There will now be a difficulty in arranging the next Seanad election, for which the graduates of NUI form a constituency. Unless of course….

and an article by Brian Lucey and Charles Larkin:ThePost.ieSet our universities free 24 January 2010

Hardly a week goes by without a government spokesman discussing an aspect of the ‘smart economy’. In the public (and perhaps government) mind, this is equated with technology. But a truly ‘smart’ economy is not based on technology, but on flexibility - especially mental flexibility.

Developing this should be the primary focus of the higher education sector. However, a set of interlinked issues render it unable to do this.

Irish higher education suffers from a conflict of mission statements. It is expected to deliver on innovation, education, social enrichment, economic growth, public health and improved lifestyles. Though research suggests that all of these - and more - arise from higher education, the effect varies across individuals and disciplines. The context is further complicated by the regional imperative.

Given the need to spread scarce funds widely, there is little chance of obtaining internationally competitive scale in any one area or institution. Higher education and innovation are also drowning in an alphabet soup: HEA, Hetac, Fetac, SFI, IRCSET, IRCHSS,HRB, EI, Fás, Forfás, NCC, IDA. . . the list goes on. Although some consolidation in qualification accreditation is now being proposed, this is only a start.

Consideration should be given to the creation of a single ministry with three divisions - education, training and employment, and innovation and research, with a minister of state with responsibility for intellectual property.

Ideally, the ministers should be appointed from the Seanad, allowing for external non-political experts to be chosen on the basis of observed international competency in these areas.

In this way, we can begin designing a holistic structure of higher education and innovation, and make real progress on eliminating many of the governance failures that currently exist, as a result of higher education and research being spread across too many government departments and agencies.

We need a visionary step forward. In the Irish educational context, we have a precedent in Donagh O’Malley’s Free Education Act - concerning the issue of secondary school access. This was met with a frosty reception from the keepers of the exchequer gates, but was a key foundation block for our modern economy and society. A similar solution is now needed for the university space.

What would such a solution entail? We suggest three main elements, implemented at the same time: freedom of academic institutions to set and deliver their own courses, quality in all aspects and adequate funding.

Academic freedom is perhaps the simplest, and yet most profound, step.

In essence, this would involve the granting of ‘university’ (ie degree granting) status to all third and fourth-level institutions (inclusive of exceptional legal entities; for example, research-orientated facilities, such as the Royal Irish Academy and the Dublin Institute for advanced Studies).

The announcement by education minister Batt O’Keeffe that he is to abolish the NUI is a first step towards this. But the road to true reform is long indeed. Each institute of technology, NUI constituent college or any other body now offering courses at diploma level or above would be freed.

Care needs to be taken that we do not replicate the failures of Britain and Australia with regard to similar reforms. In institutes of technology, new programmes go through a very rigorous evaluation. The issue is that existing programmes need root-and branch reform to ensure that they are of the same quality and intellectual standard.

With freedom comes responsibility, and the most important responsibility will be to offer educational programmes aligned with the fostering of flexible minds. Freedom of this sort would allow universities to determine their own courses, to play to their own research and teaching strength, to plan their own futures and to compete in the market for education based on these strengths.

Freedom should be extended to faculty wages. At present, within narrow bands, the best are paid the same as the worst, the most active the same as the least. Universities must be able to set wages based on the demand for the faculty and on the excellence or otherwise of its job performance.

Evidence from the US indicates that salary freedom can assist in incentivising staff, but this can arise at the cost of over-reliance on casual and adjunct lecturers at the undergraduate level. The cost of ‘superstar’ researchers must not be borne by the undergraduate programme. The US Marines have a motto, ‘Every man a rifleman’. We need to ensure that, in the newly-freed institutions, a motto of, ‘Every scholar a teacher, every teacher a scholar’, is taken just as seriously.

Freedom must also, of course, mean freedom to fail. If a university were unable to deliver on required educational outcomes, then it ultimately would be required to fold or to be subsumed by another more successful university - and mechanisms need to be created to deal with the fall-out if it happens.

We suggested earlier that a truly smart economy involves the production of flexible thinkers. Such an education must be more than purely discipline-focused at third-level. There is little point in producing graduates who are scientifically illiterate or unaware of human or social sciences.

We can broadly consider three domains of intellectual activity in universities: humanities, letters and the social sciences (arts); life sciences; and natural sciences. A true university education would involve an annual minimum of 15 per cent engagement with each domain. Specialist or technical knowledge required for entry into some (but perhaps not all) of the professions is best achieved by well-rounded graduates choosing postgraduate programmes in these areas.

To provide these postgraduate courses adequately, all academic staff in the university would be required to research actively, which would be achieved by a rolling tenure system.

This would involve the granting of tenure for a prospective five to seven year period, with biannual reviews.

A recent court decision (Cahill v DCU) highlighted the need for a legallybinding definition of tenure, granting immunity from dismissal by reason of pursuit of unpopular, unfashionable or dissenting research, and which would be automatically subject to measurable and externally verifiable outputs.

Research activity and research quality are only loosely related, but quality requires activity as a prerequisite.

To ensure quality of teaching we suggest that there be biannual reviews of teaching based on best modern practice. This would involve some element of student feedback, but also reflective portfolios and classroom observation. To oversee this quality issue, we suggest a single evaluation unit within the above suggested ministry.

A third element relates to funding. The economic argument for public funding of universities is that they are providers of public goods - well-educated citizens. The Irish rationale for full public funding was principally for narrow party political gains. Separating undergraduate from postgraduate education allows greater clarity to emerge.

People seeking to take Masters or doctoral qualifications in an area do so for one of two reasons - a desire to seek entry to an area or profession (investment), or one of personal interest (consumption).There is no obvious reason why the government should fund the latter over other consumptions.

In any case, the operation of the tax/PRSI system should, in most circumstances, offer a return to society, partly via the increased taxable earnings that better-qualified persons achieve, thus capturing the ‘public good’ element of an increase in, for example, dentists, telecommunication engineers or doctors of literature.

Research can continue to be funded through internal allocation of surplus funds from running such courses, from philanthropic and competitive sources.

What then remains is the extent to which society wishes to fund the cost of undergraduates. With a restructuring such as we recommend above, some element of public funding is appropriate, given that it would result in a greater alignment with the needs of a modern economy and society.

However, some payment at the point of use - fees - is required. These fees can either be paid upfront at a discount, deferred and repaid via the tax system or paid via social transfer for students who qualify for a grant.

As a starting point, consider 50-50 burden sharing - universities should produce a full economic cost of their undergraduate provision, and then retrospectively be funded half of this en bloc by the state.

The consequence would be differential fees for courses in the same university and across the university sector. When combined with the freedom to offer such courses and directions as desired, and a CAO-like entry system, a system of student place allocation could combine financial incentives and academic integrity. Such a set of solutions is radical. It requires bravery in facing up to entrenched vested interests in politics and universities. It requires a willingness to be frank with the public.

Whether this can be achieved in the Irish political system is dubious, but the role of leaders is to lead.

Charles Larkin is research associate in the school of economics, and Brian Lucey is associate professor in the school of business, Trinity College Dublin

© Thomas Crosbie Media 2010.0 -

I'm sure there is but that doesn't necessarily mean that all individuals who score less than, for example, 300 points are unable to manage a high workload or possess a high intelligence quotient.donegalfella wrote: »This post has been deleted.

I agree on the point about the LC not being challenging enough but I would mention that the regimented rote learning encouraged by the leaving cert does not sit well with many students. I only say this because I earned 335 points (not that good or bad) but as soon as I entered the college environment, my results and workload drastically increased simply because the college 'style' of learning suited me far better.donegalfella wrote: »I frankly don't accept the "Secondary school didn't challenge me, and that's why I got 200 points in my Leaving" argument. If secondary school hadn't challenged you, you would have walked away with 600 points and made it seem easy.0 -

Only two of the NUI colleges actually have NUI in their title (NUIG and NUIM).

Presumably they regarded membership as being more beneficial than UCD or UCC.

Even if NUI is abolished, would there be anything to prevent Galway and Maynooth from continuing to refer to themselves as NUIG and NUIM ?0 -

Advertisement

-

Do you disagree that from 1998 through 2000 that points for many computer and technology related degrees were far higher than they are now or have been in the last 7-9 years. Do you agree that if this was so that it's possible such courses would have produced more higer grades in the period of 2002-2004? You say that the increase in grades was probably among Arts and Commerce courses? I'm curious as to why you have singled these courses out?

I don't think it's possible to disagree with the first point! Numbers enrolling in computing/electronic engineering doubled rapidly from 1996 to 2001. However, what you're looking at there is a high water mark of about 1900 students enrolling per year in all third level courses across the country in 2001, up from about 900 in 1996, and what we're interested in is the enrollment years that result in graduation from 2002 to 2004, which is 1998-2000. The increases in those years - about 200 students per year - is completely insufficient to explain the rise in higher class honours, even if every single one of them achieved a First, since enrollment across the degree granting institutions alone was about 55,000.

On top of the issue that the numbers of extra students in computer-related fields is insufficient, we have the question of whether those students did do better, and if they did, by how much.

cordially,

Scofflaw0 -

I'm sure there is but that doesn't necessarily mean that all individuals who score less than, for example, 300 points are unable to manage a high workload or possess a high intelligence quotient.

I agree on the point about the LC not being challenging enough but I would mention that the regimented rote learning encouraged by the leaving cert does not sit well with many students. I only say this because I earned 335 points (not that good or bad) but as soon as I entered the college environment, my results and workload drastically increased simply because the college 'style' of learning suited me far better.

The rote learning problem remains my single major concern about educating my child in Ireland. I don't want my daughter to struggle to get into university, but I don't really want her to be too good at rote learning either. The A-level system in the UK had its own drawbacks (choosing your academic path at 15, for a start), but it did encourage the same kind of learning as is needed for university.

cordially,

Scofflaw0 -

This post has been deleted.0

-

Numbers enrolling in computing/electronic engineering doubled rapidly from 1996 to 2001. However, what you're looking at there is a high water mark of about 1900 students enrolling per year in all third level courses across the country in 2001, up from about 900 in 1996, and what we're interested in is the enrollment years that result in graduation from 2002 to 2004, which is 1998-2000. The increases in those years - about 200 students per year - is completely insufficient to explain the rise in higher class honours, even if every single one of them achieved a First, since enrollment across the degree granting institutions alone was about 55,000.

The increase wasn't just seen in electronic engineering but all computer related disciplines too - physics (theoretical, experimental, with electronics etc.), mathematics, computer science, IT, etc. The building boom was on the way and civil engineering was on the rise. Biotech and biomedical science and engineering were on the rise, driven by the economic climate and somewhat by increasingly higher medical entry requirements, with alot of people who missed out settling for biomed for the time being.

I'm not saying that the increase in points in these types of courses is definitely the sole cause of the rise in 1sts and 2nds but it is something to bear in mind. Proof of the effect, or non-effect, of these trends would be seen if data on the % of 1sts and 2nds by discipline were available. If there is a decline in 1sts and 2nds over the next 3/4 yrs, it may also indicate that this was a factor.0 -

T.W.H Byron wrote: »No, but you were implying that there is a correlation between high leaving certificate points and a high iq. Perhaps there is one, maybe not.

Just because there's a correlation between high points and intelligence doesn't mean that all intelligent people get high points and that all less intelligent people get low points, it just means the average person will tend to get more points than an average person of lesser intelligence.

What is most certainly doesn't mean is that everyone with under 300 points is dumb and everyone over 500 points is a genius. Actually, anyone with over 500 points who believes the previous sentence is false definitely proves my point for me.0 -

The increase wasn't just seen in electronic engineering but all computer related disciplines too - physics (theoretical, experimental, with electronics etc.), mathematics, computer science, IT, etc. The building boom was on the way and civil engineering was on the rise. Biotech and biomedical science and engineering were on the rise, driven by the economic climate and somewhat by increasingly higher medical entry requirements, with alot of people who missed out settling for biomed for the time being.

I'm not saying that the increase in points in these types of courses is definitely the sole cause of the rise in 1sts and 2nds but it is something to bear in mind. Proof of the effect, or non-effect, of these trends would be seen if data on the % of 1sts and 2nds by discipline were available. If there is a decline in 1sts and 2nds over the next 3/4 yrs, it may also indicate that this was a factor.

The numbers I've used are for all computers and electronics related courses (from an HEA study regarding their post-2001 decline), and cover all "third-level" institutions without regard to degree/diploma status - if anything, therefore, they're a slight overestimate compared to the number of students in degree-awarding institutions.

The numbers simply don't add up - only if every student on a computer-related course got a First in 2004, having not got one in 2002, could you even begin to make an impact of the right order of magnitude (but still lower than the actual change).

You've a lot more work to do to make that explanation stick, whereas the fact that the NUI colleges changed their grading system by lowering the marks required for higher degree grades over the period of the grade jump is both a sufficient explanation and a proven fact.

cordially,

Scofflaw0

Advertisement